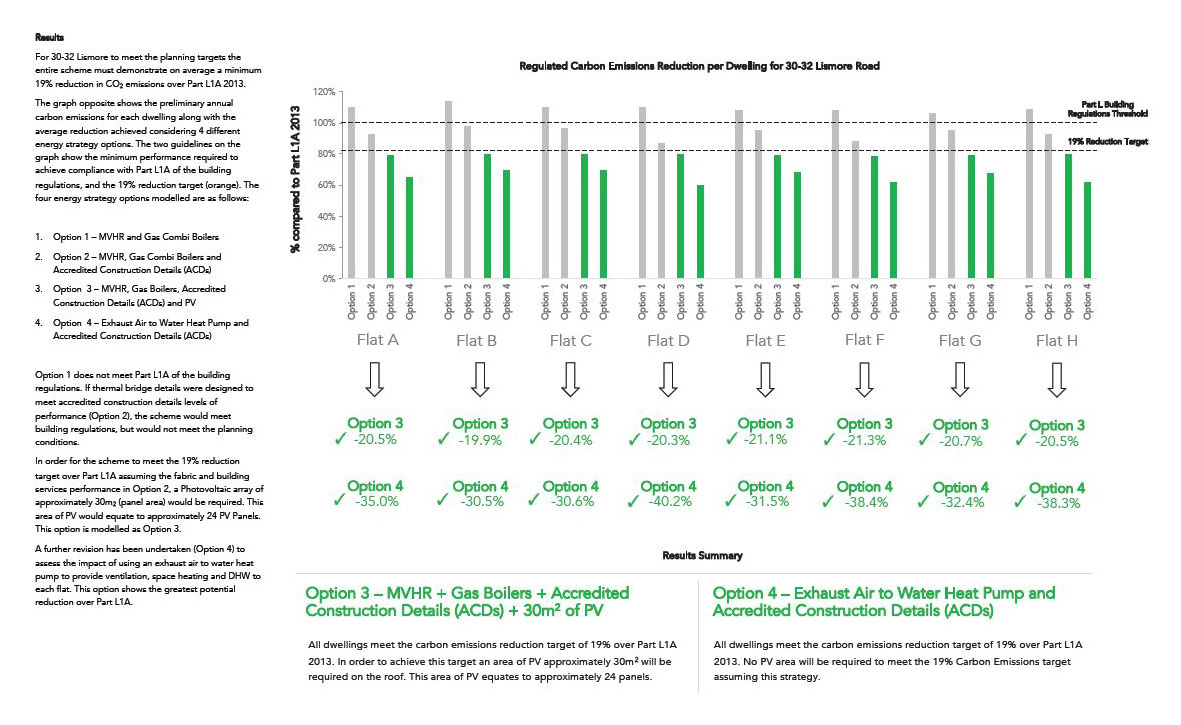

We are often asked if we have built sustainable developments before, and how did we do it whilst sticking to a ‘reasonable’ budget. Our best built example of this is Chalkhurst Court in Croydon, a block of eight apartments which we completed in 2019. The overall contract value for the construction was £1.25m which works out at £2,100 per sqm, but the specification for the development was still extremely sustainable, for example we met the Passivhaus standards for the external building fabric. Whilst we were assisted in this by a very proactive developer/contractor client, we did work very hard with them to make the most of the budget. Below is a summary of the four key strategies we implemented during the project.

Energy efficient construction

The part of a building that remains in place for the longest is the building fabric, and so the priority should always be to ensure this is as high quality and energy efficient as possible. This comes from a combination of construction method, product specification and detailing. At Chalkhurst Court we worked with the Passivhaus Consultants Etude to create the most energy efficient building possible within a reasonable budget as follows:

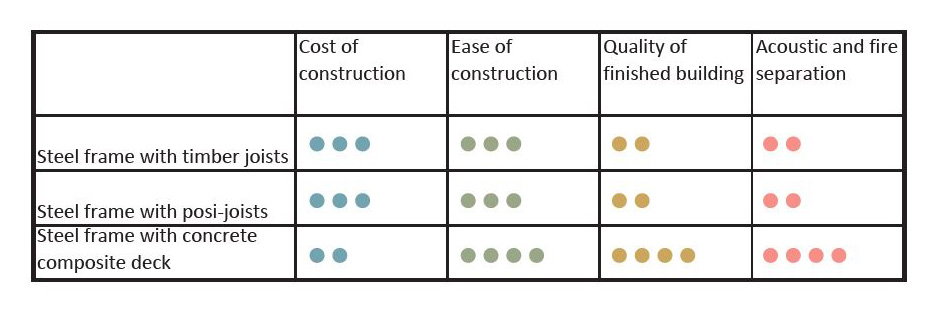

Primary Structure – At Tate+Co we nearly always specific timber-framed buildings, but at Chalkhurst Court we settled on a steel and concrete construction. This was because we had both a limited budget for the building and an overall height restriction from the planning permission. Meeting the acoustic and fire requirements is obviously possible with a timber frame but it involves more complicated build ups which means deeper floor construction depths and greater costs. The below table sets out our final decision making process. With our greater knowledge of embodied carbon now, I think we might have made a different decision, but at the time in order to afford the performance requirements we wanted to achieve we needed to go for a more ‘conventional’ primary structure.

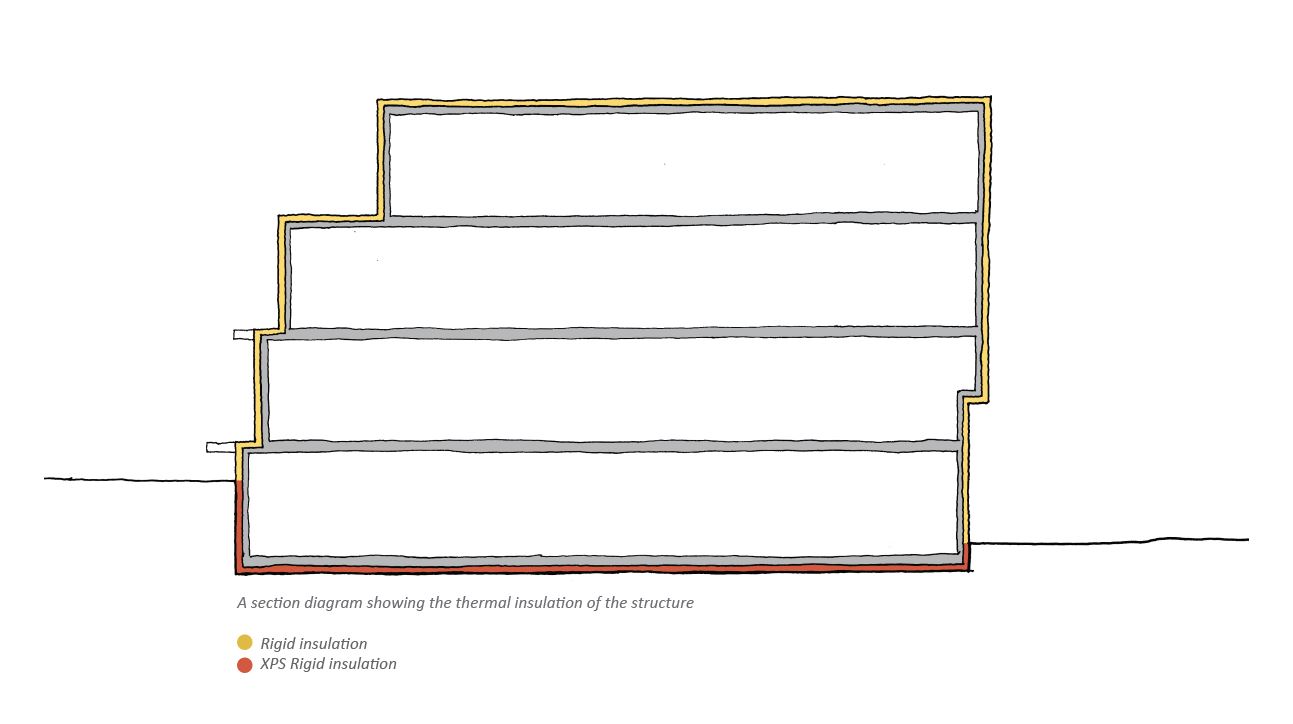

High performance building fabric – The thermal performance strategy we worked out with Etude needed a well insulated and air-tight construction. We specified Passivhaus levels of insulation whilst not going for actual certification. This translated to the below requirements:

Walls – U-value of 0.13 W/m2K

Roof – U-value of 0.12 W/m2K

Ground slab – U-value of 0.12 W/m2K

Windows – U-Value of 1.2 W/m2K (including frame)

Air tightness – 3 m3/hr/m2@50Pa

We also designed the layer of insulation to fully ‘wrap’ the building as a continuous layer on the outside of the building which creates a ‘tea cosy’ effect of efficiently keeping the heat in the building.

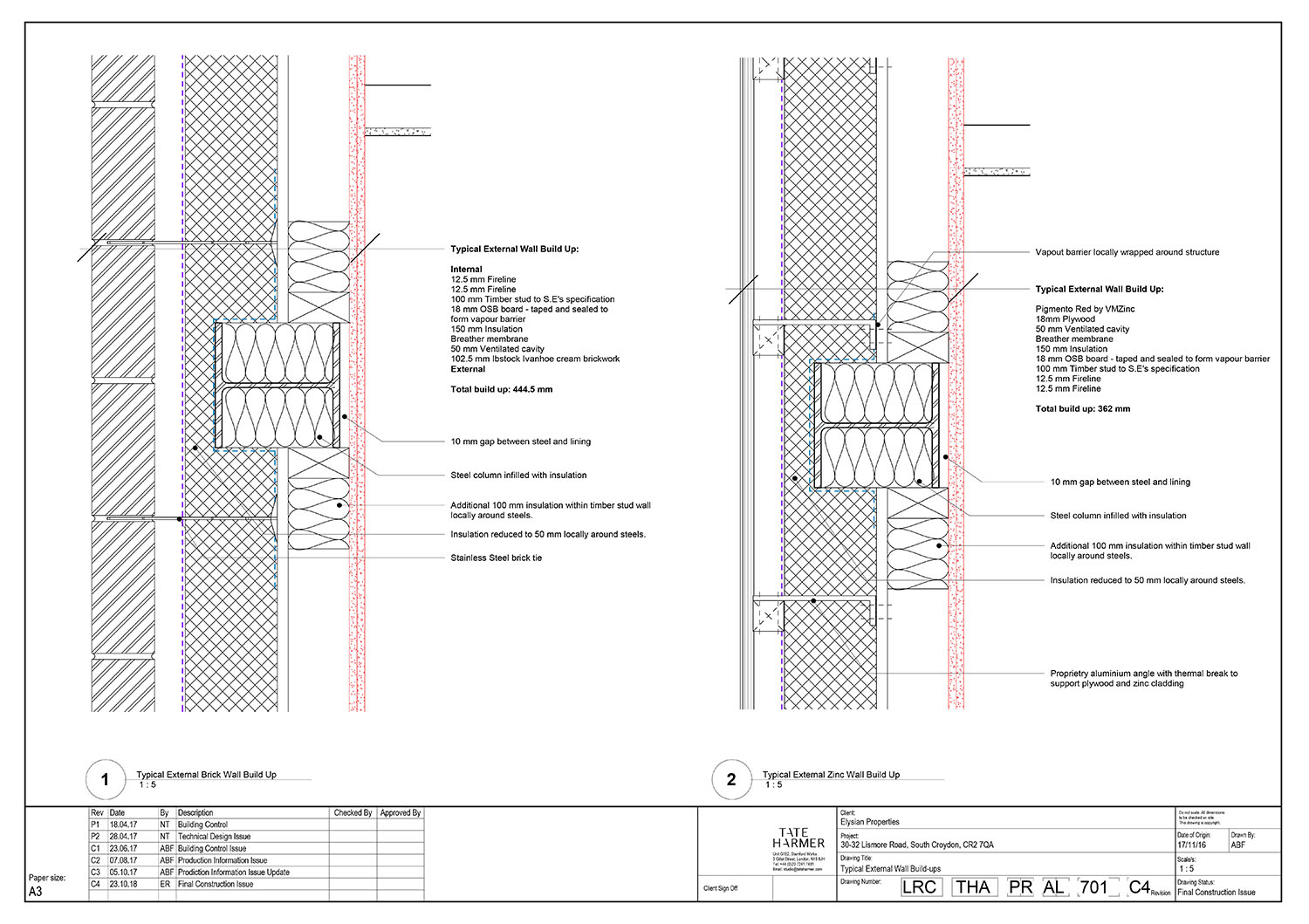

The below drawing and photo shows the typical wall build up we used to achieve a 0.13 W/m2K U-value. Although the external cladding was brick, to tie in with the local context, the construction behind was a timber framed wall fully filled with insulation. This enabled us to create a high level of insulation within a reasonable wall build up thickness of 445mm. It was important to keep the external walls reasonably thin to maximise the internal areas of the apartments within the fixed extents of the planning permission. There are two things to mention here: Firstly, with a more unconventional construction method like this (as opposed to brick and block) it is important to complete a dew-point calculation to ensure there will be no moisture problems within the wall. Secondly, on a related issue, it is very important to avoid ‘cold-bridging’ where part of the wall can conduct heat, for example in the below drawing you will see we have carefully encapsulated the steel column with insulation.

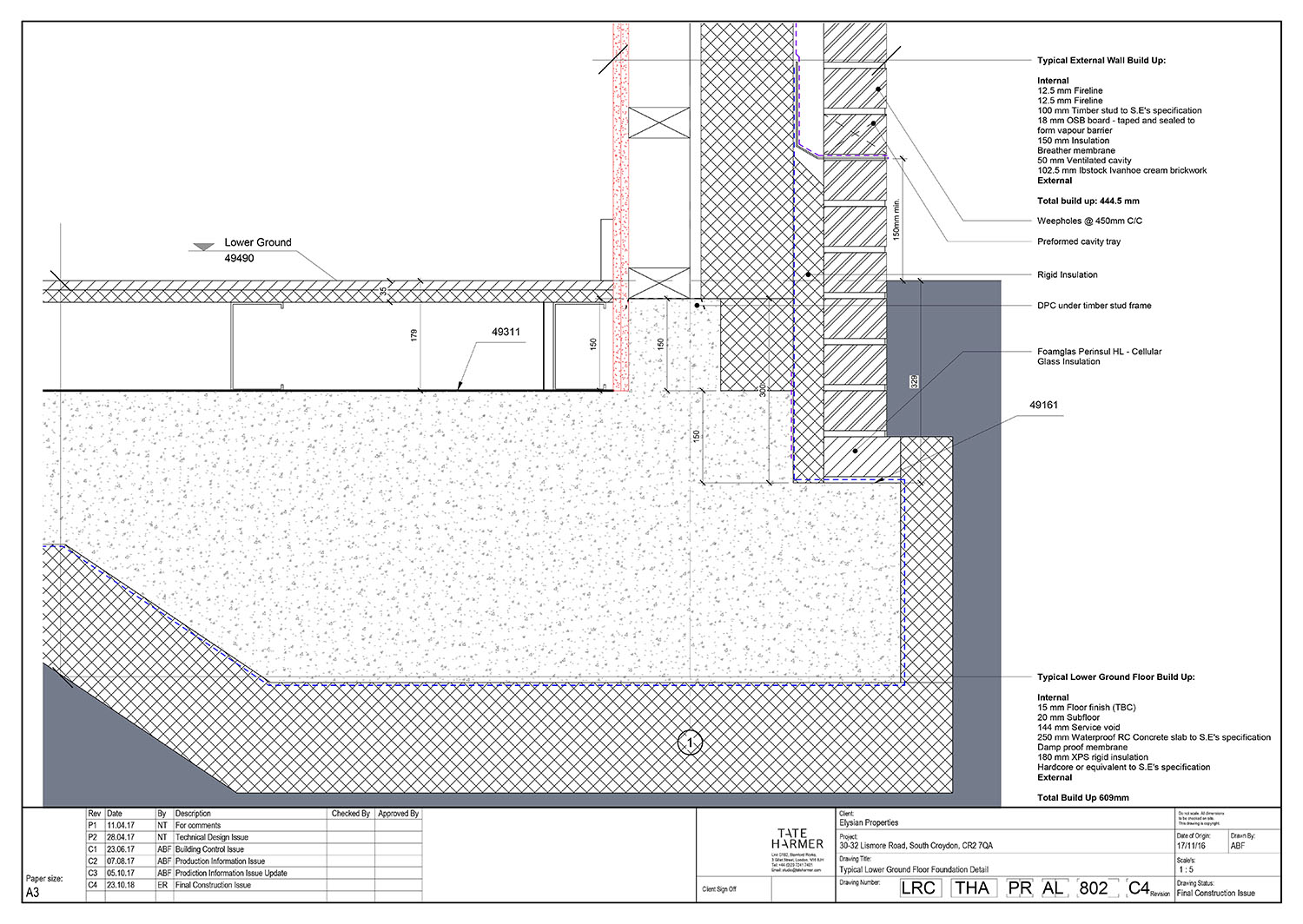

The drawing below shows the build-up for the ground slab to achieve a 0.12 W/m2K U-value. For this project we were building on chalk and therefore did not require piles, so we opted for a reinforced concrete raft slab solution. There are two thermal advantages for this, the first being that with the right specification and detailing we can fully wrap the slab with insulation as shown in the below detailed; the only potential cold bridge to the slab is the support for the external brick wall which we mitigated with a Foamglass Perinsul HL structural thermal break. The second thermal advantage for this detail is that the entire concrete slab is inside the thermal envelope of the building which creates an excellent thermal flywheel effect (keeping heat or coolth inside the new homes).

Integrated services strategy

Once you have established how you are going to create an efficient external building fabric the next step is to develop a sustainable servicing strategy for the building that works well for your building performance. Etude thermally modelled the building during the design process so that we could precisely understand what the building required and ensure it created a comfortable internal climate.

We considered a number of different primary heat source and ventilation options, with the lowest predicted carbon outcome being from an Exhaust Air to Water Heat Pump with integrated Mechanical Ventilation Heat Recovery (MVHR). These are units around the size of a tall fridge, one for each apartment, that are both an air source heat pump and an MVHR system. This means that they supply all the heating and hot water for the apartment, as well as fresh air with a heat exchanger to ensure no heat loss. As this uses electricity for the primary heat source, these units can also potentially be part of a zero carbon solution (depending on how the electricity is procured). The key practical advantages of these units are; that you do not have external AHUs for the heat pumps; and that the apartments have fresh air supplied all the time without necessarily needing to open the windows. As there is a dedicated unit for each apartment we also satisfied our developer/contractor client’s desire for each apartment to have their own individual heating system (they were concerned about the perception of communal systems when selling the homes). Keep in mind that Exhaust Air to Water Heat Pumps are quite tall and the units need to remain vertical so it is important to work out the installation logistics with your contractor early in the process.

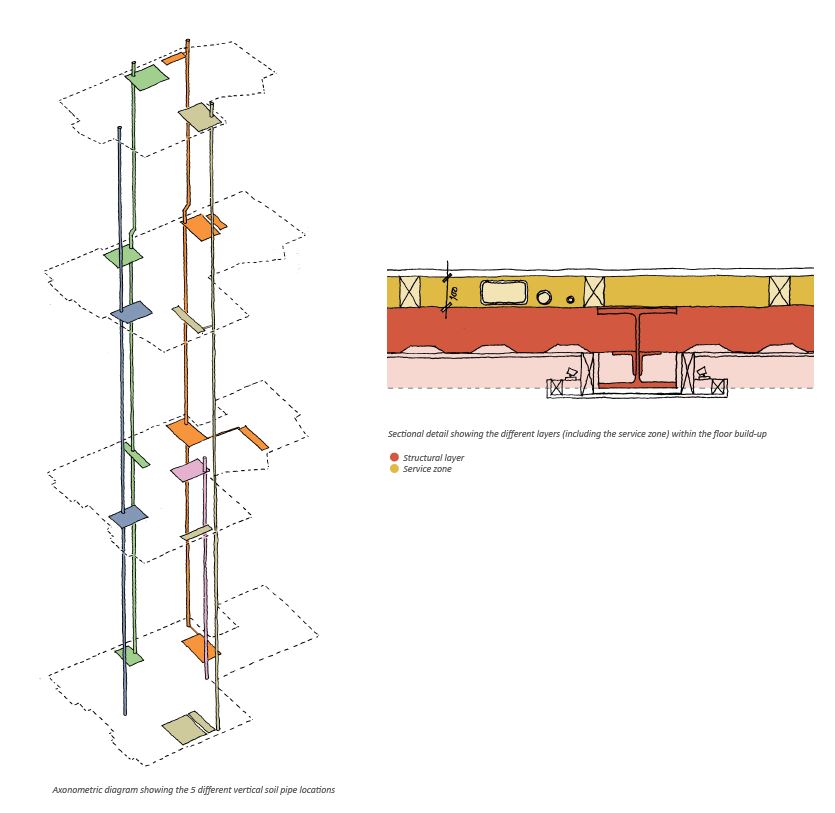

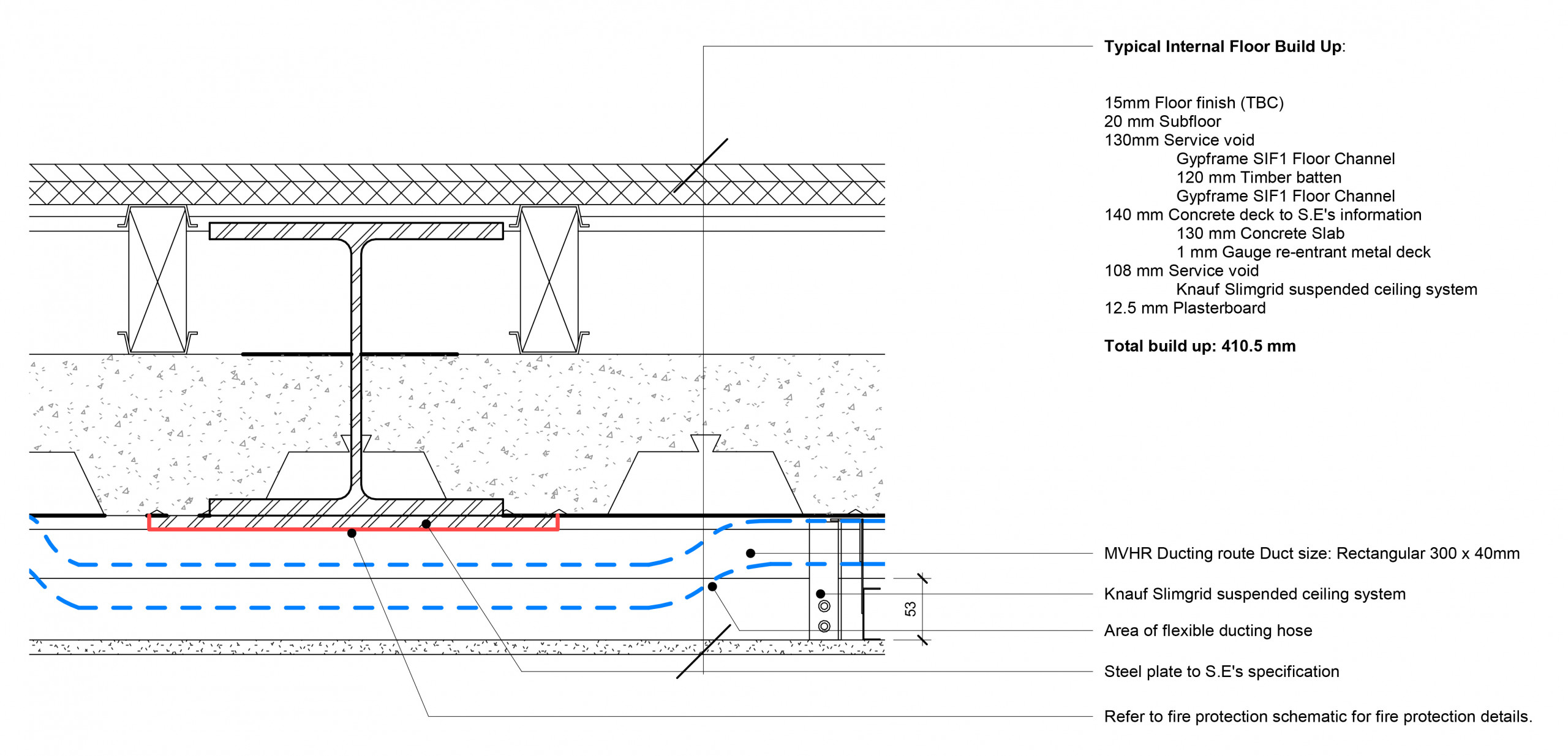

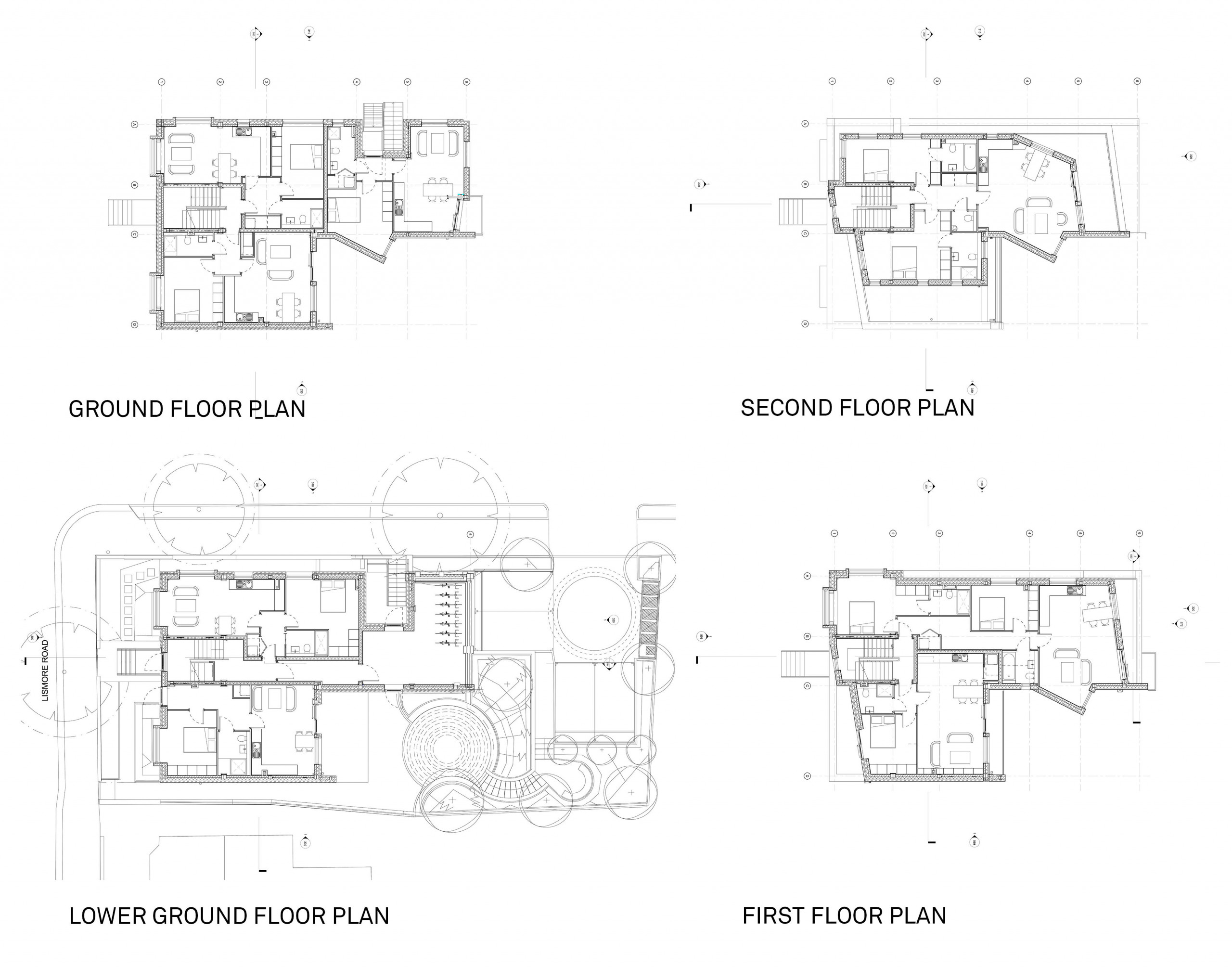

To ensure the heating and ventilation systems worked to their optimum, with the least spatial impact (ie reduction in floorspace or ceiling height) we very carefully considered how all the services would pass though the building. We partly achieved this by vertically aligning the heavily serviced areas of the building so that we could limit the riser sizes. But we also detailed the primary structure so that there were no steel down-stands below the composite concrete deck; this ensured a clear run above the plasterboard ceiling for the MVHR ducting, as well as a service zone below the floor finish to accommodate electrical wiring. Through careful attention to this structure and services integration we achieved a 410mm overall internal floor depth (i.e. from finished floor to finished ceiling). This meant that although the planning permission and site context restricted the height of the building, we still achieved very decent 2.6m high spaces throughout.

Good quality living spaces

Whilst the quality of the internal spaces may not seem strictly an energy saving measure, it is definitely a sustainable measure as it can have a direct impact for the health and wellbeing of the occupants. Although we were working in a very restricted site and context we still strived to create a variety of different apartment types that maximised space, natural daylight, privacy and access to individual outside spaces. Storage was integrated into all the designs and the layouts were carefully considered. The ground floor apartment was fully accessible for wheelchairs users with level access from the front garden.

Some aspects of a quality design also do have an impact on energy consumption. For example the majority of rooms have windows on different sides of the space and whilst this does improve the ‘feel’ of a space, it also creates more even daylight spread, thereby reducing the artificial light needed, and allows for better natural ventilation in summer months, which improves comfort levels. Finishes choices can further assist with this, we generally chose a natural and light material palette for the building, with finishes that helped bring light deep into the apartment interiors; for example Dulux Light and Space paints which have a reflective additive.

The relationship between living areas and private external spaces can also really help lift the quality of an apartment. At Chalkhurst Court we designed a series of individual external spaces which were tailored to create very private outside areas, with good views across the surrounding suburban landscape. The key aim was to create truly usable spaces that the residents can genuinely envisage occupying as part of their day to day life.

Landscape and communal spaces

This brings me on to the fourth and final part of what we considered at Chalkhurst Court to create a truly sustainable development – the quality of the internal and external communal space. The thoughtfulness and quality of this can really assist with residents’ health and wellbeing, as well as helping them to live a more low-carbon lifestyle.

Due to the sloping nature of the site we realised early on in the design process that we could both simplify the foundation system we were planning on using as well as creating a semi-basement to the rear of the building (we were aided in this calculation by the assistance of the developer/contractor client). This created sufficient internal space for good quality, indoor secure bike parking, and, most importantly, a small external space for bike-washing and maintenance. We also created dedicated internal storage areas for the apartments, similar to the French concept of ‘caves’ that they tend to include in their apartment buildings. This allows residents to really ‘flex’ how they use their apartments in terms of changing furniture or possessions to cope with inevitable lifestyle shifts during their lives.

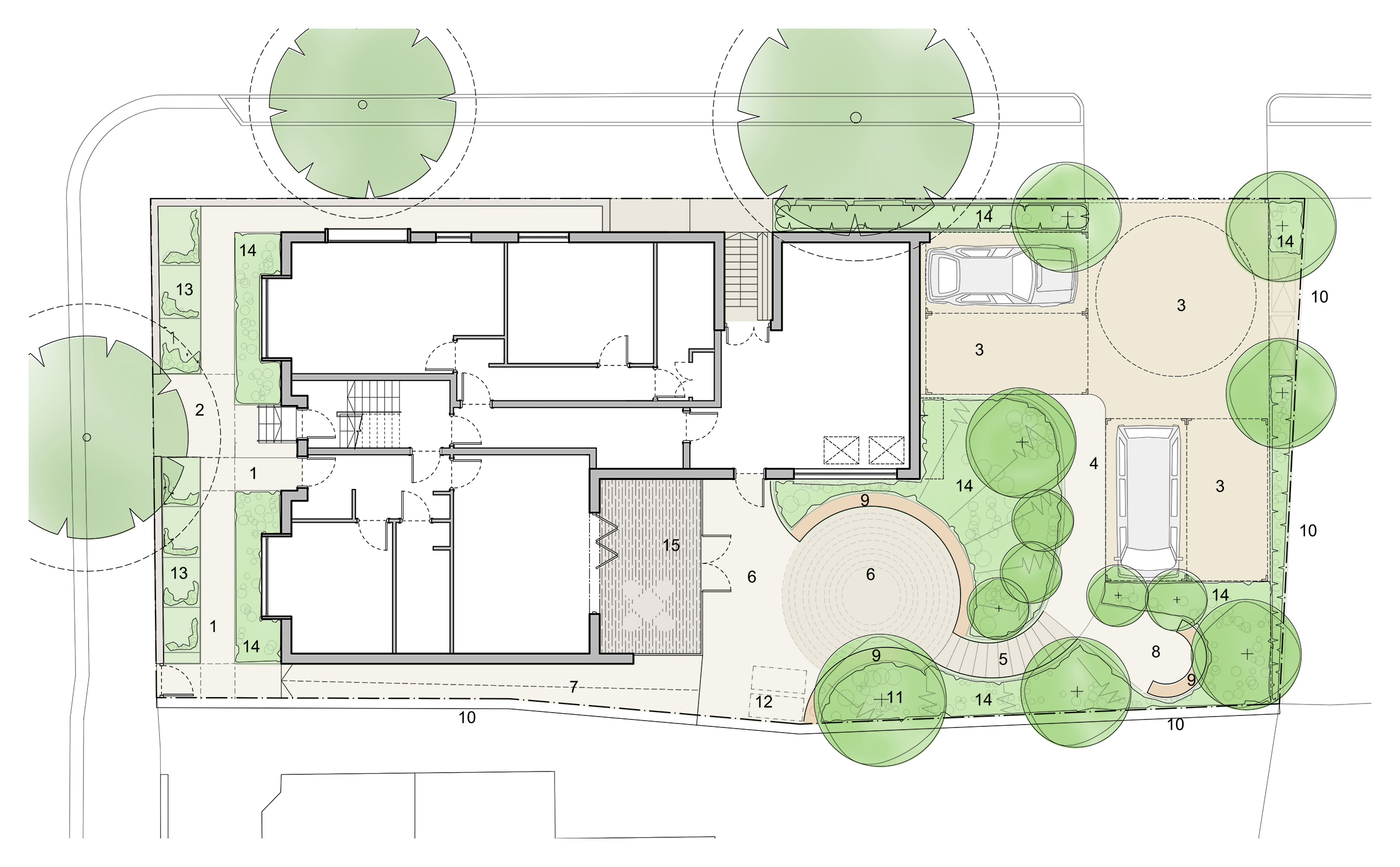

We wanted to create external communal landscape spaces in the sheltered garden of the apartment building that residents can really use and which feel comfortable. To maximise the space available to create this space we used an external turntable to reduce the size of the car park we needed to meet the Local Authorities parking requirements. We brought in landscape architects Adams Habermehl who cleverly worked with the levels to create a series of sitting terraces that each created a semi-private areas for residents to use.

It is always hard to balance pragmatic and budgetary constraints against the desire to create a sustainable development. I genuinely believe that the decisions we made on this project struck a good middle ground that delivered a financially viable product that is still good for the planet. The final thing to mention is that all the apartments were sold almost immediately which shows that people can tell when there are quality homes available.

Jerry Tate

Director

Jerry founded Tate+Co in 2007 and maintains a central role at the practice. He is driven by his desire to generate creative, pragmatic and unique solutions for each project that have a positive impact on our built and natural environment. Jerry is influential across all projects, ensuring design quality is paramount.

Jerry was educated at Nottingham University and the Bartlett, where he received the Antoine Predock Design Award, subsequently completing a masters degree at Harvard University, where he received the Kevin V. Kieran prize. Prior to establishing Tate+Co, he worked at Grimshaw Architects where he led a number of significant projects including ‘The Core’ education facilities at the Eden Project in Cornwall, UK.

Jerry is an active member of the architecture and construction community and a fellow of the Royal Society of the Arts. He is a member of the London Borough of Waltham Forest Design Review Panel and is frequently invited to lecture, notably at Education Estates, the Carpenters Fellowship and Ecobuild, as well as contribute to architecture publications, including the Architects Journal, Building Design, Sustain, and World Architecture News. He has taught at Harvard University, run a timber design and make course for the Dartmoor Arts organisation and was Regnier Visiting Professor for Kansas State University’s Architecture School in 2021/22. Currently Jerry teaches at the Bartlett School of Architecture, UCL.

In his spare time Jerry is involved with a number of charities and is a trustee at the Grimshaw Foundation as well as a Governor at Cranleigh School.