At Tate+Co we seek to create positive, learning environments for universities and independent schools. On top of this, Jerry Tate, Founder and Director here at Tate+Co, is a Governor at an independent school so knows first hand these are challenging economic times for many education institutions. This article sets out three strategies that, when you have financial constraints, make sense of how to maximise the positive impact of your campus.

We hope you find it interesting and if you would like to join the conversation, please do get in touch!

We would love to hear from you.

Strategy One: Make sure you have the right sized campus

At Tate+Co, a key first step is to check if an institution’s campus is the right size. You can check this using the following approach:

Step 1: Measure the area of your existing estate

This can be achieved through desktop exercises, physical surveys, or a mixture of both, and will provide valuable insights into how your estate is used and the mixture of different spaces you currently have.

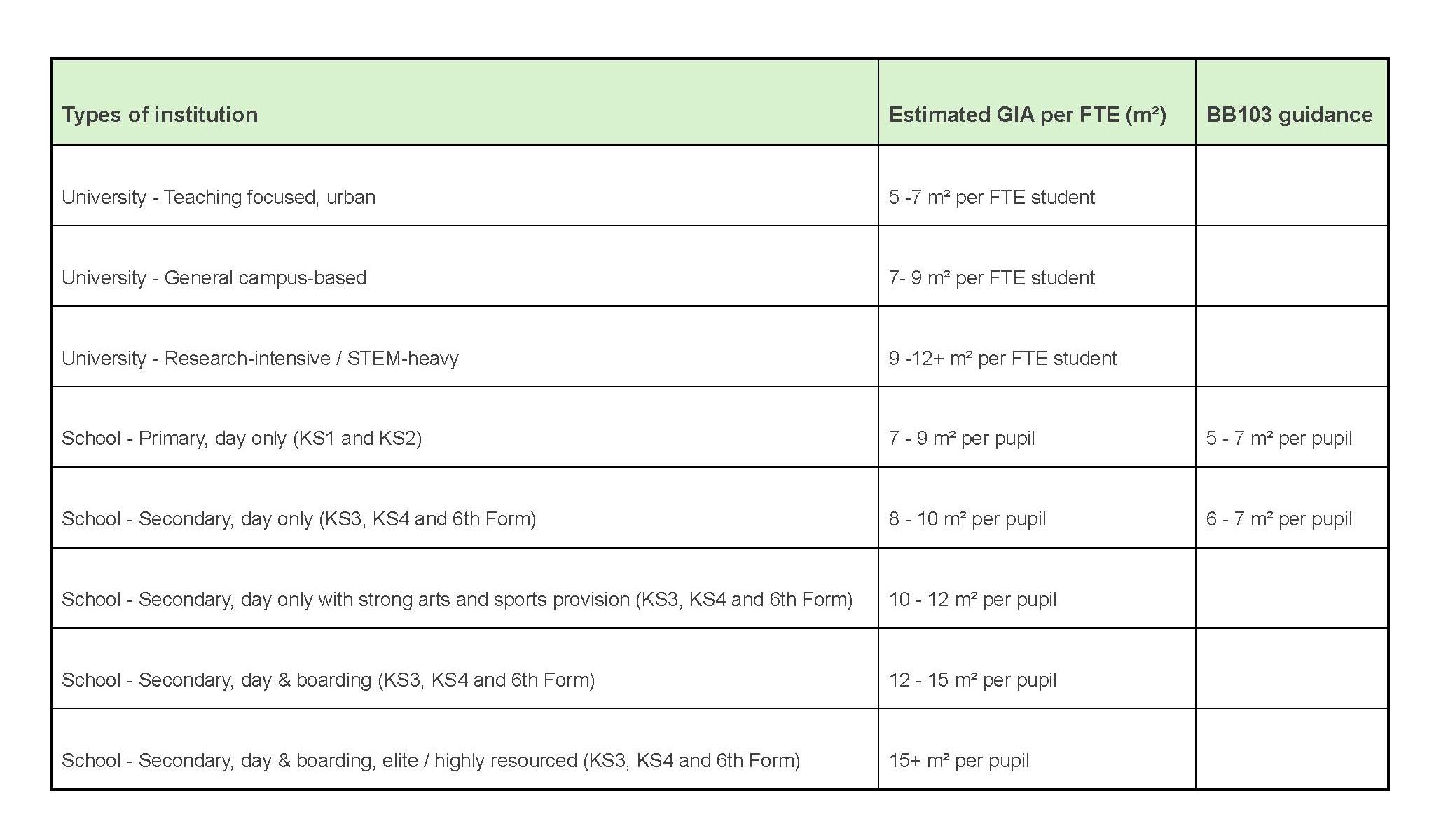

Step 2: Benchmark your estate

Armed with a list of areas and overall size, you can now benchmark your estate against other similar estates. We often complete a desktop study of institution’s competitors to see if they have comparable facilities (you can do a lot on Google Earth). And there are spatial benchmarks to check if you have too much or too little space. Below are some guidelines based on a combination of our experience, and research by AUDE (Association of University Directors of Estates) ISBA (Independent Schools Bursars Association) and Department for Education spatial guidelines (BB103):

Step 3: Develop an aspirational brief for your institution

An aspirational brief can be developed through a series of conversations with all key users and stakeholders. For a school this could include teachers, the senior leadership team, pupils, parents and local community members. For a university this could include the Executive Office, the estates team, academic department heads, the Student’s Union, local businesses and community groups. The outcome of the consultation should be a shopping list of ideal spaces and areas that will form the basis for your new estate masterplan. (By the way, this also ties in with the Strategy Two.)

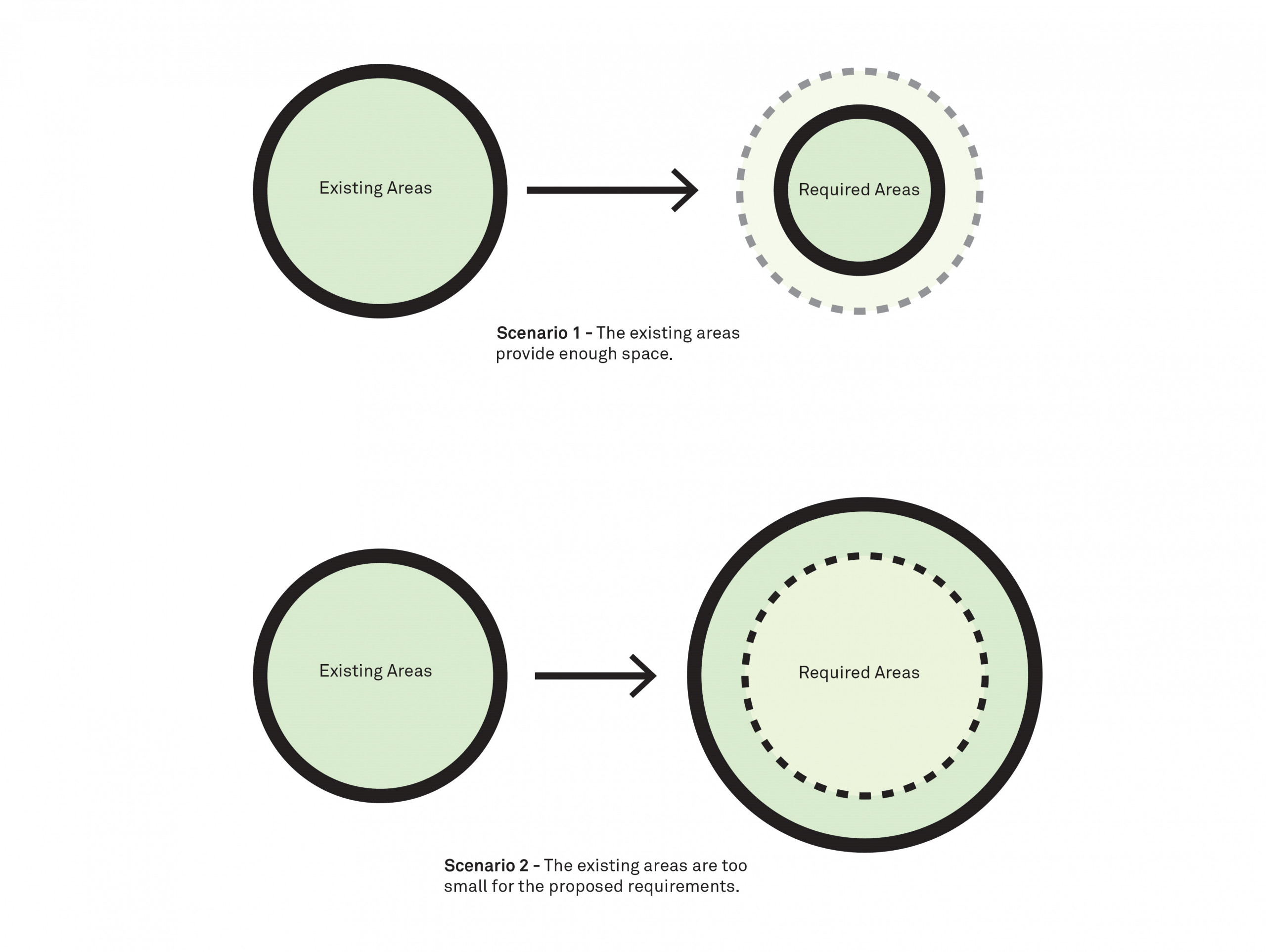

Step 4: Compare your ideal spatial requirement with your existing campus

It might be that you have exactly the right sized campus (in which case congratulations!). But in our experience, it is more likely that your campus is either too big or too small. If it is too small, you may need to consider expanding. But I would stress that it is almost always possible to improve spatial efficiency through reconfiguration and improving utilisation rates. The real opportunity however comes if your campus is too big, because then you can consider leasing or selling parts of it to release extra capital, this can provide a financial lifeline or funding for future development and improvements.

Strategy Two: Focus on your student experience

The second strategy when facing challenging times is to make sure you are providing the very best student experience, both generally and in specific learning environments. For schools or universities this is definitely not a luxury. It may seem crass but in the end your students are your ‘customers’ and a bad experience will mean reduced attendance, applications and learning outcomes. Improving the student experience does not necessarily mean large capital outlays if you follow these steps:

Step 1: Complete a student survey

Your student body probably knows what they would like, and what does not work at the moment on your campus. There are many different ways to gather information on this; as part of a consultation process we have been involved with online surveys, physical meetings, social media campaigns or specific websites set up to gather comments. The key step is to analyse the data once you have it to create overall themes. For example, your on-site food and beverage offer might not be up to scratch, but dissatisfaction with this might be expressed in many different ways ranging from wanting to eat off-campus, to straight up complaining about bad food.

Step 2: Complete an ‘experiential survey’

This is a technique which has been pioneered in the transport and hospitality sectors, but we are now seeing it increasingly used in the education sector. Essentially it is a photographic survey moving around your campus, following the route of different types of students, team members or visitors. Realistically you want to pick a maximum of five different types of people. By taking photographs at key points in your ‘journey’ through the site you can identify when the experience ‘drops’, for example where there is a particular low quality area, or where the wayfinding is bad.

Step 3: Create a ‘shopping list’ of projects

Using the data gathered from the first two steps you should be able to generate a ‘shopping list’ of potential projects. Our advice here it to limit these to range of 10 to 20 projects, and for each one to write an initial brief and (if applicable) area schedule. It is worth stressing that a project could be as simple as re-decorating a hallway, installing a sign, or repairing a floor. At the same time projects could encompass more significant elements like a new refectory or renewed / reconfigured teaching stations. It is good practice to put an estimated cost against each project, or if you are unsure, work with a Quantity Surveyor to help you produce these.

Step 4: Pick the ‘low hanging fruit’

Once you have created your costed ‘shopping list’ you should prioritise the projects. Normally we find that at least 25% of things which would dramatically improve the student experience can be completed within your annual capital and / or maintenance allowance, so these are the ‘low hanging fruit’. Getting these projects completed as soon as possible will indicate to students and staff that your institution is healthy, and cares about their learning experience.

The images above are of the Townsend Building, Cranleigh Preparatory School. Promoting the school’s philosophy of healthy, outdoor living, the building was designed with no internal corridors. Classrooms were designed to provide direct access to covered, outdoor space.

You can find out more about the project here.

Photography: Kilian O’Sullivan

Strategy Three: Connect to nature as much as possible

The final strategy to consider when you are operating with limited financial headroom is to maximise connections to nature throughout your campus. There are clear and proven benefits to this, for example the University of Salford’s 2014 report ‘Clever Classrooms’ demonstrated that increased ‘naturalness’ in classrooms can promote 16% better educational outcomes in students at primary school level. But achieving a better connection to nature might be easier than you think and you can almost certainly afford to implement at least one of the following ideas:

Idea 1: Introduce plants into your campus

Indoor plants can help with student and staff wellbeing and concentration and, to a certain extent, indoor air quality. The key point with indoor plants is to specify them carefully, generally forest floor plants work best as these need less daylight and water to survive and are therefore more robust. Also try to group plants over your campus rather than spreading them everywhere as this reduces the maintenance burden.

Idea 2: Make sure your windows can open

Pretty much all windows can open somehow, even if they might be stuck or need adaption. There are often acoustic or mechanical ventilation reasons given to keep windows closed, but an overwhelming majority of building occupants generally prefer the idea of natural ventilation. The ability to open a window can have massive benefits in terms of giving teachers and students a feeling of control over their own learning environment.

Idea 3: Make the most of any outside spaces

If you do have outside spaces, you can dramatically improve them by thinking about creating a ‘pocket park’. This can be as simple as introducing potted plants. Even if people do not often use outside areas, they can have a real impact on how an interior space feels.

Idea 4: Paint your spaces to make then brighter

You can bring daylight much deeper into a space by repainting it bright colours. Specifically there are now a number of special reflective paints available such as Dulux Light and Space. These maximise the amount of natural light throughout an interior and can also save you energy; on average they mean that artificial lighting is required for 30 minutes less every day.

Idea 5: Get more daylight into your spaces

The final, and possibly most expensive idea, is to introduce more daylight into a space by installing additional windows or rooflights. To really improve the experience of a space, one should consider how to create an even spread of daylight, so ideally you would provide increased daylight from a different direction than the existing windows. This might even be ‘borrowed’ light using an internal window. Additional windows or rooflights can also help increase cross natural ventilation which relates to Idea 2.

The images above are of the Creative Centre York St John University. An outdoor view can have a positive effect on levels of concentration. The landscape-led masterplan at The Creative Centre also increased planting and within the first phase of the development delivered a 54% increase in biodiversity net gain.

You can find out more about the project here.

Photography: Hufton + Crow

Conclusion

In challenging times, it is important to make sure you still create the very best learning and collaborative environment for staff and students, especially in an increasingly competitive world. The majority of the above strategies are relatively low cost, but potentially high impact in setting a positive tone for your institution.

Jerry Tate

Director

Jerry founded Tate+Co in 2007 and maintains a central role at the practice. He is driven by his desire to generate creative, pragmatic and unique solutions for each project that have a positive impact on our built and natural environment. Jerry is influential across all projects, ensuring design quality is paramount.

Jerry was educated at Nottingham University and the Bartlett, where he received the Antoine Predock Design Award, subsequently completing a masters degree at Harvard University, where he received the Kevin V. Kieran prize. Prior to establishing Tate+Co, he worked at Grimshaw Architects where he led a number of significant projects including ‘The Core’ education facilities at the Eden Project in Cornwall, UK.

Jerry is an active member of the architecture and construction community and a fellow of the Royal Society of the Arts. He is a member of the London Borough of Waltham Forest Design Review Panel and is frequently invited to lecture, notably at Education Estates, the Carpenters Fellowship and Ecobuild, as well as contribute to architecture publications, including the Architects Journal, Building Design, Sustain, and World Architecture News. He has taught at Harvard University, run a timber design and make course for the Dartmoor Arts organisation and was Regnier Visiting Professor for Kansas State University’s Architecture School in 2021/22. Currently Jerry teaches at the Bartlett School of Architecture, UCL.

In his spare time Jerry is involved with a number of charities and is a trustee at the Grimshaw Foundation as well as a Governor at Cranleigh School.