We are often asked what exactly is embodied carbon and, more specifically, what is the difference between the ‘Upfront’ and the ‘Whole Life’ figure.

Our colleague Nikita Schweizer addresses these questions in the following article.

Embodied carbon is a measure of the total carbon that has been released into the building as a result of the construction and maintenance process. The units for this measure are kgCO2eq/m2 ie:

- The weight of CO2 or equivalent greenhouse gases released

- Per Gross Internal Area of a building (GIA) in m2

There are two potential values for this figure, the ‘Upfront’ figure and the ‘Whole Life’ figure.

Upfront Embodied Carbon is all the emissions associated with the construction of the building or project up to its completion and occupation (ie extraction, manufacture, installation and construction).

Whole Life Embodied Carbon is all the carbon emissions associated during its lifetime, (normally assumed to be 60 years), excluding operational carbon.

The reason both figures are important to understand is so that you can ensure any carbon savings made through materials’ choices at the outset of the project do not have a negative impact later on due to maintenance or durability concerns.

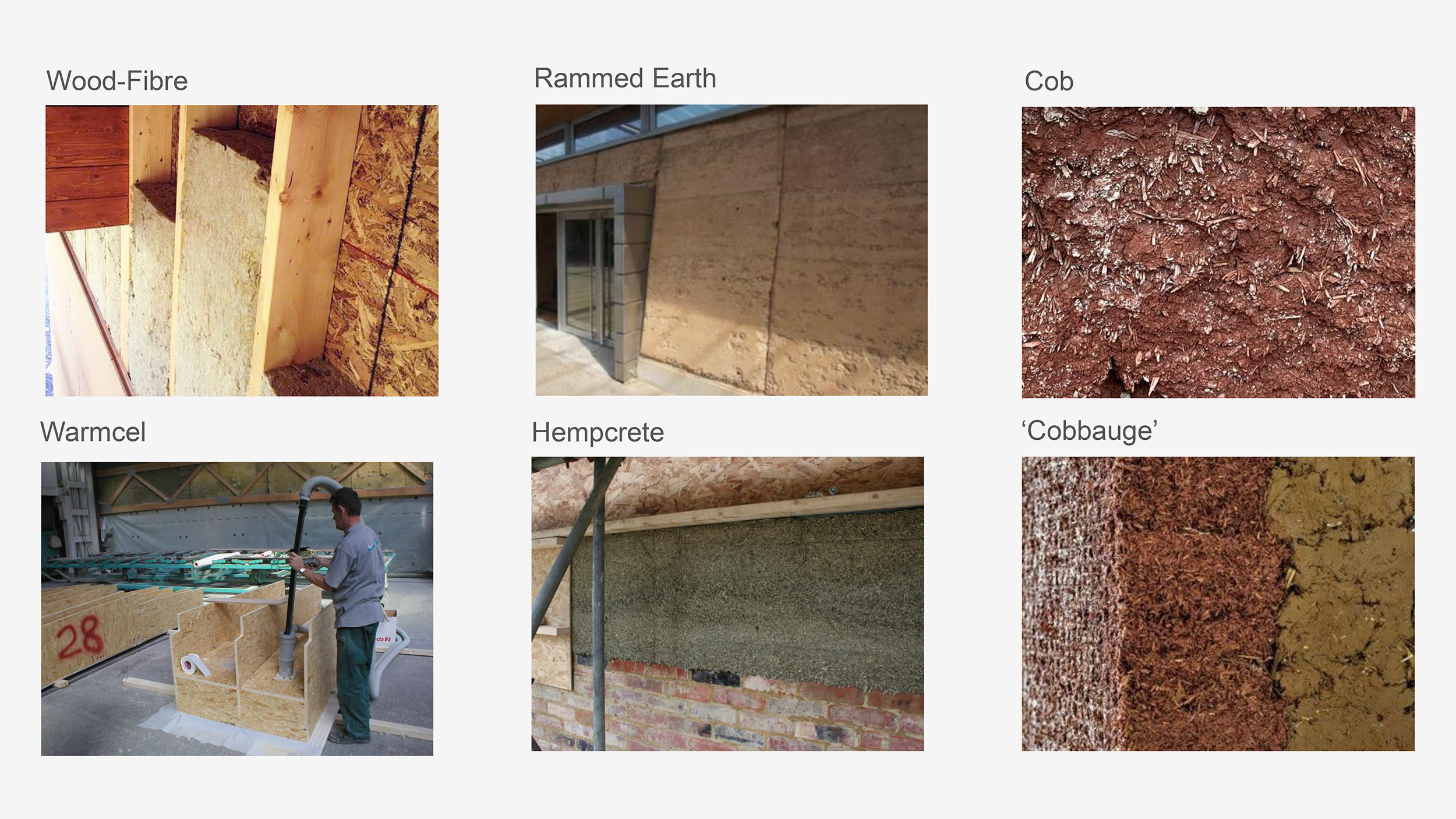

As a rule of thumb natural or recycled materials like those shown above have a lower embodied carbon content than other materials. Buildings for different sectors can have different requirements meaning only certain embodied carbon targets are achievable. See the table below showing upfront carbon embodied targets for Business as Usual (BAU), LETI and RIBA Climate Challenge 2030 targets:

For simplicity, please note the above figures are for new-build structures. Refurbishments and retrofits should have lower embodied carbon as you are using an existing structure.

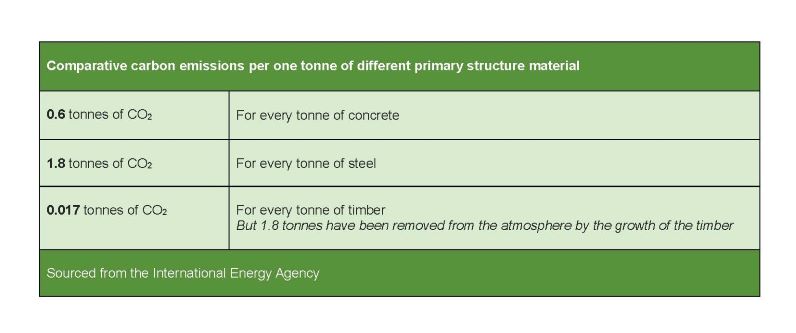

Your Architect, Quantity Surveyor or increasingly your Structural Engineer should be able to calculate your embodied energy figure during the design stage of the project. This will be based on quantities of materials and their carbon content so the figure will be more accurate as more detailed design information becomes available (ie later on in the project). The key thing to bear in mind here is that different materials can have dramatically different carbon content. For example, below are the comparative amounts of carbon emissions for one tonne of different primary structure materials (sourced from the International Energy Agency).

As an illustration, based on the above figures, you can see that choosing timber as your primary structure can dramatically reduce the embodied energy of a building. If you want to compare the carbon emissions associated with different specific products or materials most suppliers now can send you an EPD (Environmental Product Declaration) which is an independently verified datasheet.

Whilst embodied carbon is only currently measured for large buildings in London (as part of the London Plan), it is almost certain that this will become a statutory requirement in the future. This should result in more buildings being retained and refurbished and better choices for lower carbon content materials.

The two images above are of York St John University Creative Centre. With a substantial timber frame and simple climate control, the new building is genuinely sustainable, both in operational and embodied carbon terms. Low embodied carbon materials, such as glulam and CLT, were used for the construction of the Centre, as part of a ‘fabric-first’ approach using Passivhaus principles to achieve a BREEAM Excellent rating.

Nikita Schweizer

Architectural Designer

Nikita joined the team in 2022 as an Architectural Assistant. She is currently working towards qualifying as an architect, and has recently completed her Part III at the University of Westminster with distinction.

Nikita completed her undergraduate at the University of Cape Town with distinction, and thereafter worked at Noero Architects (SA) and Haworth Tompkins (UK). She lived in Germany for two years while studying an M.Sc. Masters in Architecture (Typology) at the Technische Universität Berlin.

She has a keen interest in cultural buildings and housing. Her thesis, titled Gender-based Housing (GBH), aimed to tackle gender-based violence through the realm of architecture.

Nikita has received a number of awards, such as the Des Baker Architectural Student Design Competition (first runner up), and performance-based scholarships such as the Boogertman + Partners Architectural Design Scholarship Award Africa.

Her work has been exhibited in Germany, Namibia, and South Africa, and she has been included in publications such as Designing the Survival Lounge (Part of the FRAU ARCHITEKT exhibition) and Co-designing The City: Architecture + Informal Intelligence.

She enjoys all things to do with making. In the office it’s models; outside it’s drawings, sewing, leather work and more.