Increasingly in a world dominated by the digital, people are appreciating the beauty of the analogue, the return of the ‘real’.

In a music industry where songs are streamed instead of bought, real music lovers go to gigs or buy records. The most popular shows at galleries are normally those with a ‘real’ connection to the artist. I recently visited the Georgia O’Keefe exhibition at the Tate Modern and it was interesting how her paintings had retained a power beyond that of Stegleitz’s photographs shown alongside her paintings. In many ways the era we are living in seems to be the conclusion of Betjeman’s ‘Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction’. Now that we can see or hear anything, anywhere, through our digital devices, we crave a connection to the ‘real’, something which has been touched by a human hand.

We are finding this more and more with the architectural work in our office, and in particular in our own assessment of designs. Fifteen years ago the architectural render was almost seen as a magical method of predicting what your building would become. They appeared slowly overnight (due to the lack of computing power), and were mystically revered by both the client and the architect as a faithful reproduction of what the project would achieve. However we are all too familiar now with the reality of a building falling far short of the original render, and indeed I believe we were frankly naive about how easy it is to manipulate a computer generated image to tell the right story. When I studied in the US I flirted for a time with ‘parameticism’ and amongst the US academics on the East Coast there was a philosophy of the ‘pure render’, untouched by photoshop. But even these were not enough to maintain my belief in the digital render.

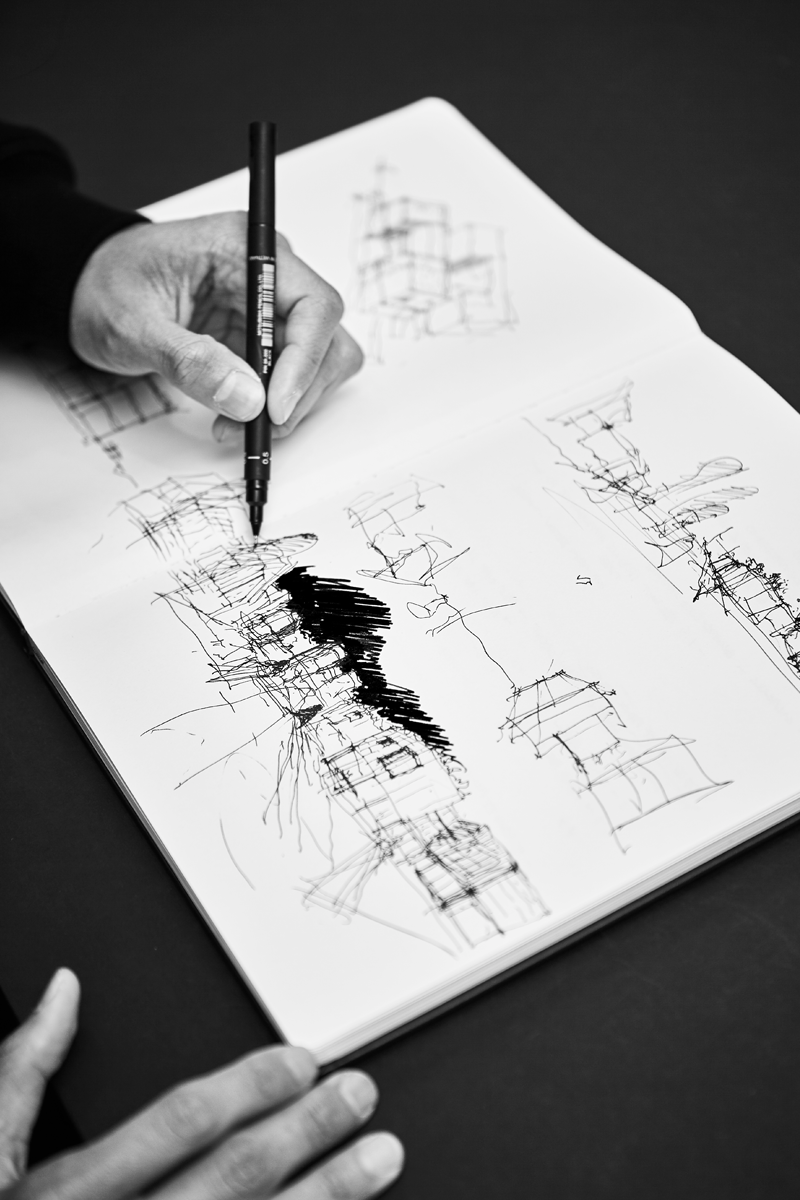

In our office now we highly value the hand drawing, the sketch model, the ‘analogue’ representation, as we find it provides an extremely valuable assessment tool for our designs. Although it can feel disruptive, getting away from the computer for a few hours can unlock difficult problems, and the speed of hand drawing or model-making in discussion is unparalleled. There is no undo button in the real world, and therefore your mode of working has to shift to an iterative process. You make something, you look at what works, then you make the next version. In this way you can swiftly evolve a design to think through the complexities of an architectural problem. I know we are not alone in using there techniques, I recently read an interview with Peter St John about his Stirling Prize winning Newport Gallery and he explained that so much of the building had been physically mocked up in their office that there were very few surprises as they built the scheme.

We also find that clients are now more receptive to our ‘analogue’ techniques. A sketch of a space truthfully implies that the design is not a finished item, and allows a non-architect to both imagine themselves into a space, as well as giving them the freedom to comment on it. A model of a space allows them to really understand, in three dimensions, what it will be, including subtleties like lighting, materiality or proportion.

Ironically as we have developed our appreciation of the ‘real’ we have re-introduced digital techniques. Many of our physical models now are hand-produced, laser-cut, 3D printed, CNC cut, hybrid productions with real vegetation as dressing. Many of our sketches now include rendered shadows, photoshopped colours and real photographic backgrounds. We find this ‘collage’ technique of architectural production intensely rich and incredibly helpful for our understanding of what we are creating.

And I think this is the key point here, the ultimate creation of what we are doing is in fact the built product. The hybrid techniques described above are more and more paralleled in the construction world, with Building Information Modelling and directly applied CNC cutting files. Everything we do during the design of our built environment should be to ensure the best possible final outcome and we should be unafraid to flip between mediums as much as we want during the design process to ensure this is achieved.

Jerry Tate, Partner