The below is an article Jerry wrote as part of his role as the 2021/22 Regnier Visiting Professor at Kansas State University for their journal (called Oz!). The theme of the publication was the ‘Discipline of Architecture’ so he wrote an article about how we see this applying to our work at Tate+Co…..mainly how we balance the creative endeavour with other pressures such as money and time, as well as the climate emergency. You can read this on the Oz website here (link), but the full article is published below.

Architecture is subject to more external pressures than any other creative practice. Would an artist expect to be so beholden to statutory regulation or overriding cost restrictions? Yet the nature of what we create, the scale of it and the impact it has on day to day lives means that we must work within the overlapping demands of our discipline, and still find ways to discover the artistry of our endeavors.

A particular new factor is the ongoing Climate Emergency and the need for our building designs to respond. If you are reading this you probably already know that the built environment accounts for 39% of global manmade greenhouse gas emissions and that unless we reduce these emissions we risk increasing the temperature of the planet to a dangerous degree. Surely this existential threat must override all other concerns when thinking about creating new, or adapting existing, buildings?

However society deserves more than a technical solution from us, it needs a vision; that in the end is our core role. Living in harmony with the planet will be something we solve with both poetry and mathematics. Architects are the only construction professionals who can bring creative balance to the design equation. Our job is to show a better future and inspire people to go there. We have the skills to demonstrate how new ways of living can give people better health, better buildings, better food, better communities and a better connection to nature. We have the overview of a project, and the understanding of the process, to be able to bring forwards a beautiful consensus, and effect positive change. We all know that the best clients understand this, and that when they demand it we are returned to the centre of the design and construction process.

But what are the challenges and why does it sometimes seem so difficult to achieve a positive change? Everybody wants to design a beautiful sustainable building that people love, so what can stop us? Well in our practice we have found ourselves using a variety of tactics to keep the essence of the creative process intact through the difficult process of delivering a building. I think this can be summarized into four key challenges.

Challenge One – Mastering technology

The first challenge is achieving mastery of the technical and technological aspects of what we do, to prevent them overwhelming the design direction. This manifests itself in two ways, in the construction process and in the architectural production process.

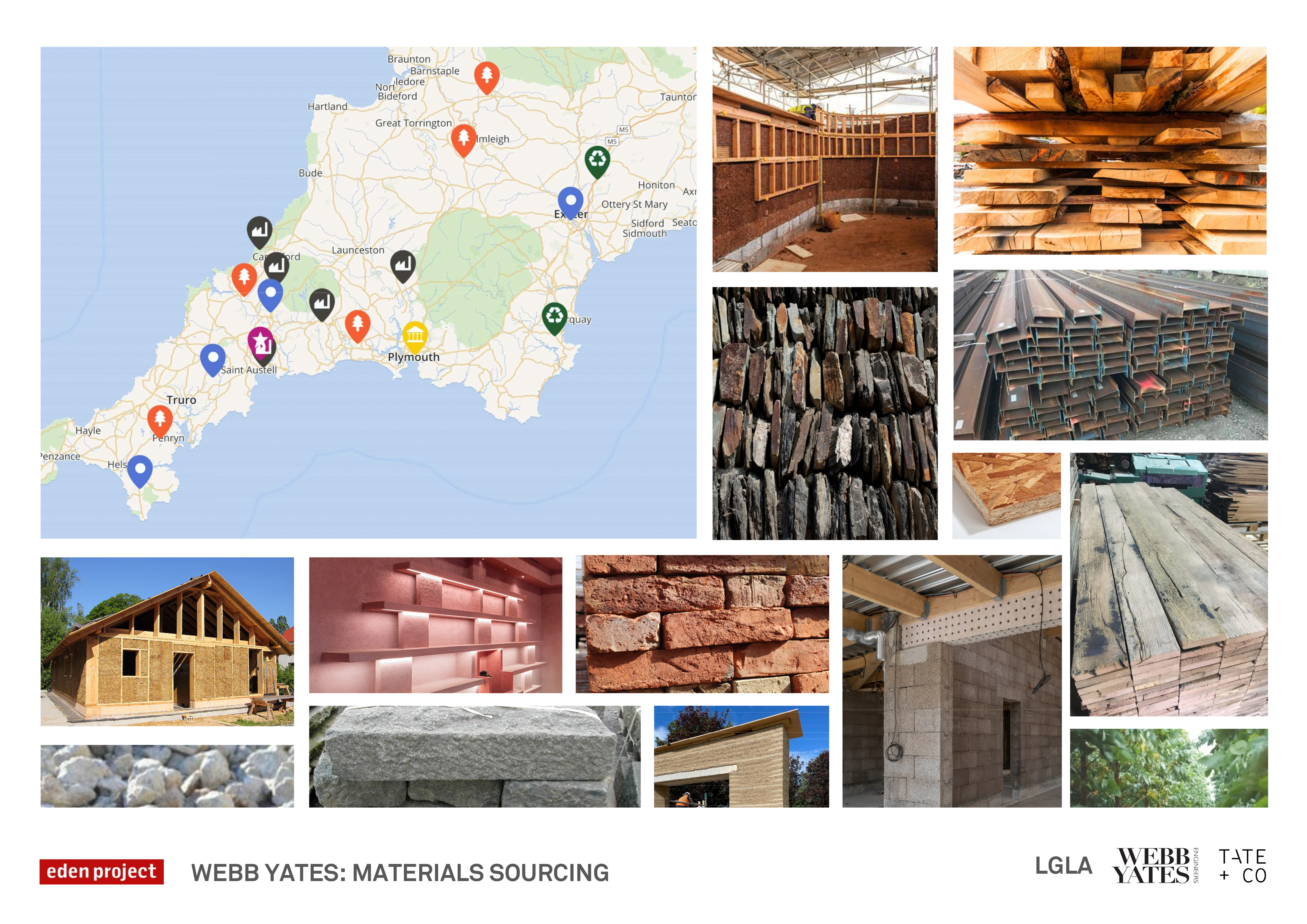

When constructing a building 200 years ago you would have needed to understand only a limited and local palette of materials and construction techniques as an architect, whereas it is now impossible to fully grasp how all the technologies within a building work. As a practice we find we are often trying to challenge ourselves to reduce complexity in the design and construction process. For example we have now started doing material maps at the start of a project to understand what local resources are available. Inevitably this means that you seek out traditional vernacular solutions to understand how they can be applied to your own contemporary situation.

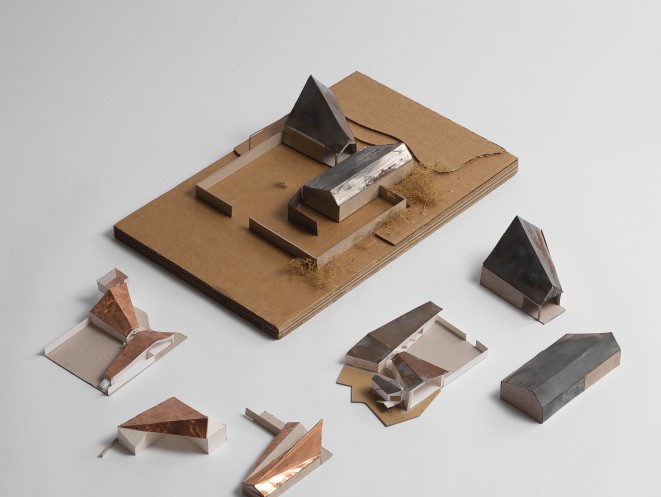

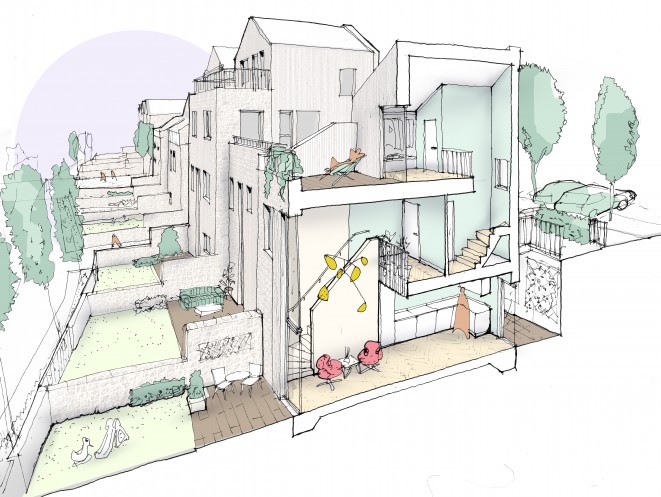

Mastery of architectural production is also an increasingly complex challenge and yet is central to controlling the design process. Over the last thirty years new technologies have enabled us incredible amounts of creative freedom, with the output of many schools of architecture far out-stripping the ability of the industry to actually construct it. But this new technology has also meant an increasingly complex realm in which we produce our designs, with both an increase in the volume of information required and a huge range of techniques and skills needed. We have found in our office that the more mediums we use to interrogate a design the stronger the final outcome. In particular, we favour a balance between the digital and the analogue. Of course we need to have a fully functioning BIM system, but we also hand-make a lot of models and hand-sketch all the time. When something as powerful as computer production is available it can become all consuming, but architecture in the end is analogue when it is built (except of course in the growing meta-verse).

Challenge Two – Keeping the central role of the Architect

The second challenge is maintaining our central position in the building delivery process. Many architects would question whether we have the power any more to effect real change in the industry, as our role has been eroded over many years. In the UK architects used to be the first person a client would call when considering starting a project and we would then remain a key part of the design and construction process from the beginning to the end. Now it can feel like we are simply another supplier, albeit of a very important element.

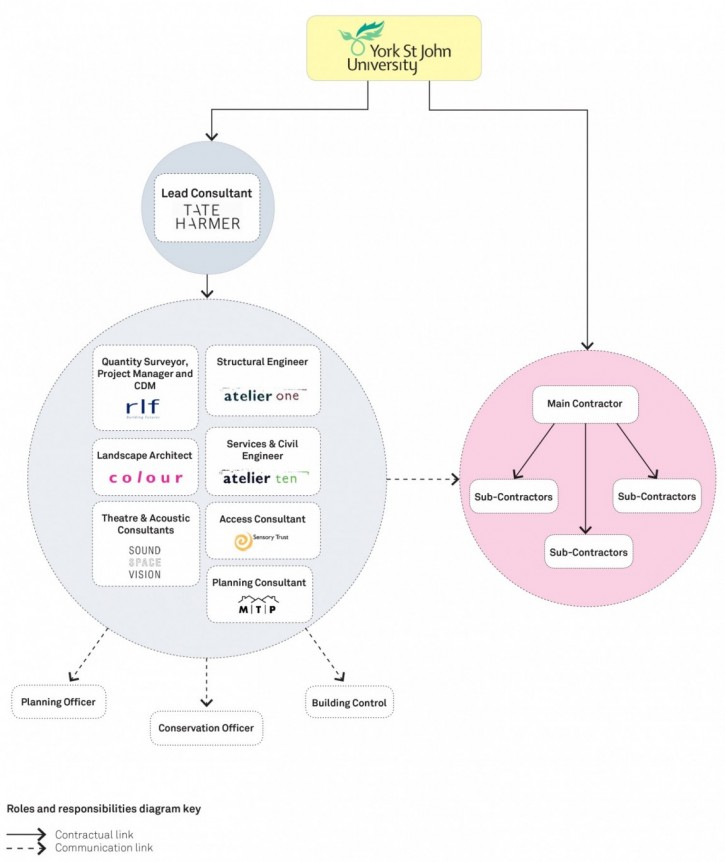

As a practice we often feel the lure of backing away from a project, reducing our liability and scope to just produce the concept design and no more. But without wishing to sound like a control freak, it is true that the best built quality outcomes we have achieved are when we have remained engaged on the project right through the construction process. For example at York St John University Creative Centre, completed in 2021, the entire design team, including the Project Manager and Contract Administrator were sub-contracted through our practice. Whilst this was a big administrative burden, an ongoing liability risk, and did not feel like a particularly creative task, the new Creative Centre is a very high-quality building right down to the smallest details and I am sure our central role contributed to this (as well as a committed client and an excellent contractor in Kier).

Challenge Three – Legislation and design guidance

The third challenge we face as a creative profession, particularly in the UK, is the increasing volume of statutory regulation, all of it written with the best of intentions but quite often contradictory or unhelpful in its effectiveness. I would categorize this into two areas, ‘hard’ legislation which is clear legal rules to be followed and ‘soft’ legislation which is the growing body of design guidance to ‘assist’ us in the design process. ‘Hard’ legislation relies on a fair and open system of application as this is the only way to understand pragmatically how it will achieve a safe built environment. In the UK at the moment there is a review of health and safety legislation following the tragic fire at Grenfell Tower in London, with one of the key suggestions being the concept of a ‘Golden Thread’ of design information that runs right through the delivery and occupation of a project. Architects could clearly be the holders of this ‘Golden Thread’ (in truth we are probably the only ones who can) but as a profession in the UK we have been slow to stand up and be counted on this front. Whilst in the USA there is still protection of function, there is no such thing in the UK, and if architects expect to regain this we will probably need to ‘lean-in’ to the ongoing debates about legislation to make our voice heard.

In the UK there is also an increasing amount of ‘soft’ legislation in the form of design guidance. All of this is written with the best of intentions and as a practice we have been involved with writing some of the guidance ourselves. There is the recently completed UK National Design Guide, supplementary design guidance at a local level and some excellent documents such as the Quality of Life Foundation Design Framework (which we assisted in the production of). I think that the content of all of these documents is generally excellent, but my concern is the growing belief that this guidance can act as a substitute for intelligent design. Every project is different, in context, community, client and ambition and it is simply impossible to completely ‘codify’ the synthesis of all of these original elements into a great design. As a practice we have a ‘magpie’ approach to design guidance (in the UK magpies are famous for taking whatever interests them to construct their nests). We like to keep abreast of all the guidance, but only take what we think is useful from each of the design guide documents to help us put together the best design solution. Often you can gain a richness from elements of design guidance, but it needs to be overlaid with a clear and strong design sensibility.

Challenge Four – Money

The final challenge is of course the understanding of money and costs in a project and how to stop these eroding your design concept and sustainability ambitions. Architecture channels large amounts of capital into a built outcome and nearly all projects have some kind of required financial outcome. It seems incredible to me that despite the importance of understanding costs in the building process architects are taught almost nothing about this in UK schools of architecture. We find that the earlier we obtain cost advice in a project, the sooner we can strategize the best allocation of costs. It is better to concentrate your resources on key parts of a building, and to achieve this you need to decide early on what matters to you in a project. For example when we completed the Invisible Worlds re-fit of the education building at the Eden Project we protected a significant amount of the exhibition budget to create one centrepiece element. The idea was that this would describe, in a visceral sense, the key idea of the Invisible Worlds theme, that there are things that are too small, large, fast or slow for you to perceive, and yet they drive the natural world. This became the incredible ‘Infinity Blue’ by Studio Swine, an 8m high ceramic sculpture based on the microscopic Cyanobacteria, which belches out smoke-rings that smell of Earth’s prehistoric past. By ensuring that the budget for this element was clearly partitioned, the project delivered an incredibly memorable experience that helped visitors immediately understand the key concepts of the exhibition.

These are all tactics that as a practice we have employed to meet the challenging restrictions of a project and still retain the essence of the creative process. Whilst it can feel like the purely creative tasks are the most important part of producing a great piece of architecture, without an excellent grasp of how to actually deliver a building you cannot make a beautiful piece of work.

Defending the fundamental principles of design

There are some fundamental principles that we believe are key to creating buildings that people will love beyond just tactics; we always remind ourselves at Tate+Co that our job is to create the following:

- Community – spaces for people

- Nature – spaces that have great daylight, fresh air, and links to landscape

- Shelter – spaces that create a comfortable environment

These three principles have successfully guided us through many projects. For example the new Townsend Building at Cranleigh Preparatory School demonstrates how an early understanding of a simple sustainability strategy can lead to a building which gives a direct connection to nature that improves the learning environment. The building is a new teaching block for Cranleigh Preparatory School to provide Art, Science and Design Technology. The site is situated at the heart of the school campus in the beautiful Surrey Hills outside London, England. The core concept for the proposal was to remove all internal corridors and give direct external access to all the classrooms. This allowed for natural cross ventilation and a good spread of daylight in all the teaching spaces, dramatically reducing energy demands for the building compared to conventional classrooms. The external circulation elements created a new deck overlooking the cricket pitch on the first floor, and a new cloister space on the ground floor that allowed more freedom of movement at the centre of the campus. With a vaulted oversailing timber framed roof, and direct views out to the landscape on both sides of the building, the design creates a direct connection with the beautiful natural setting and a calm and warm learning environment for the children.

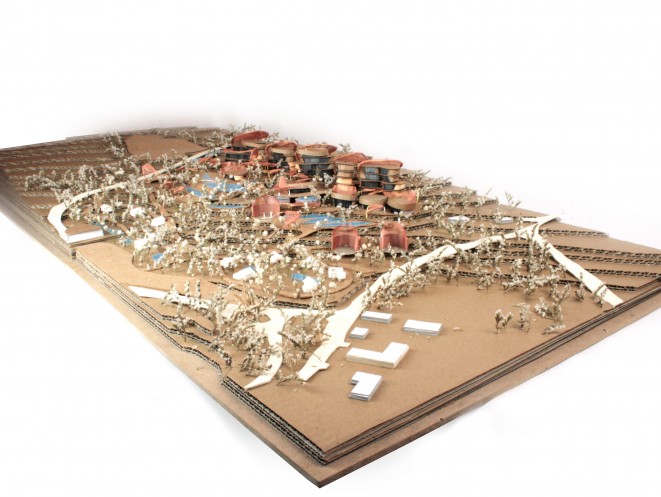

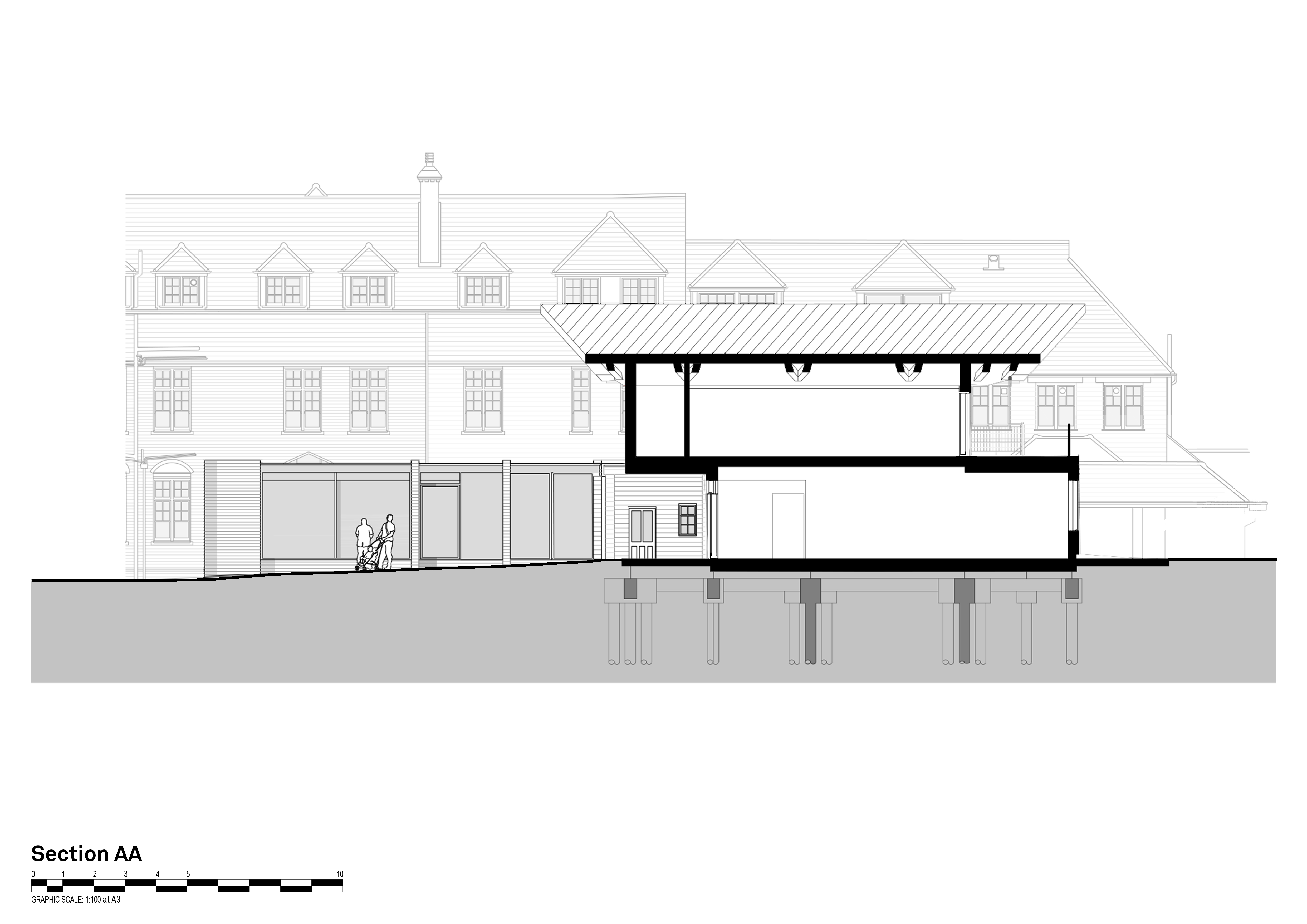

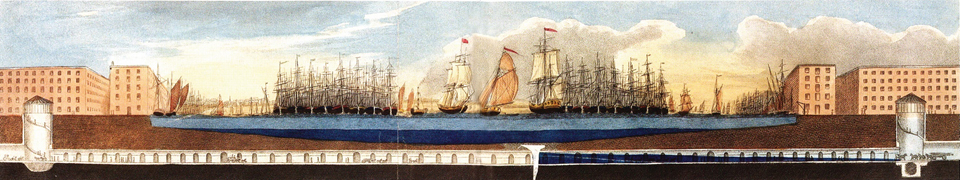

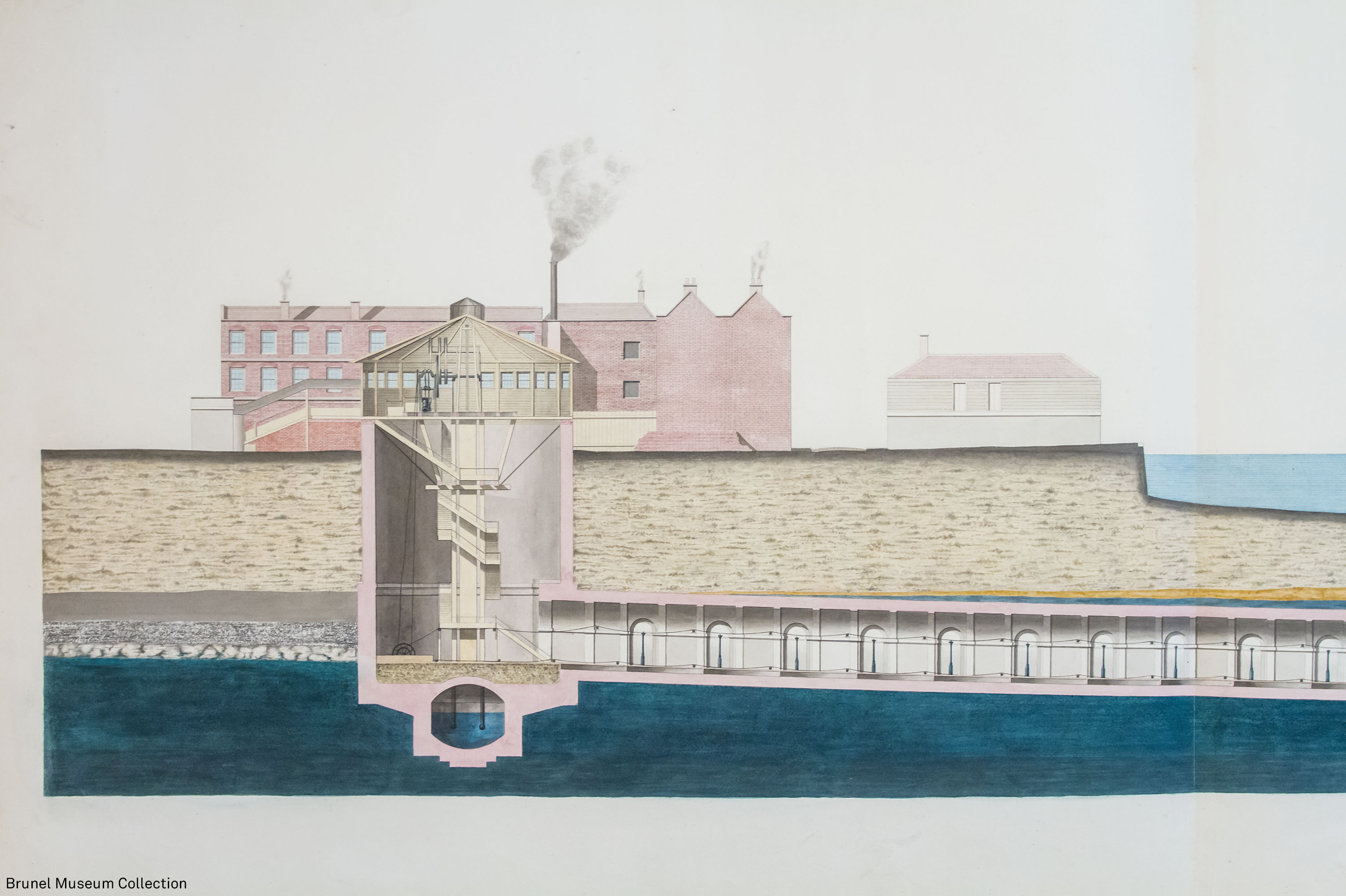

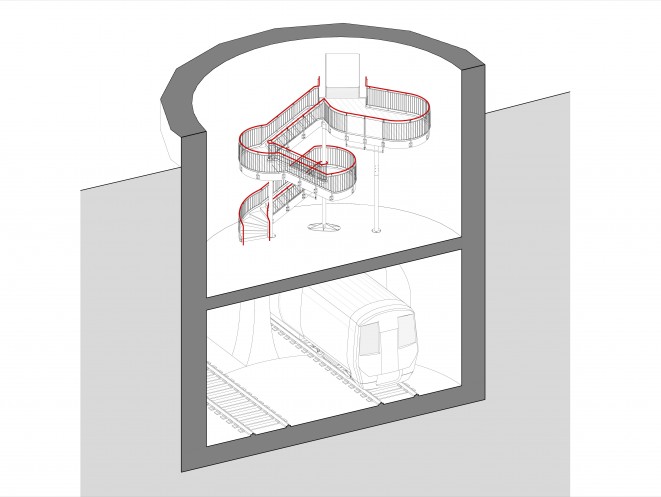

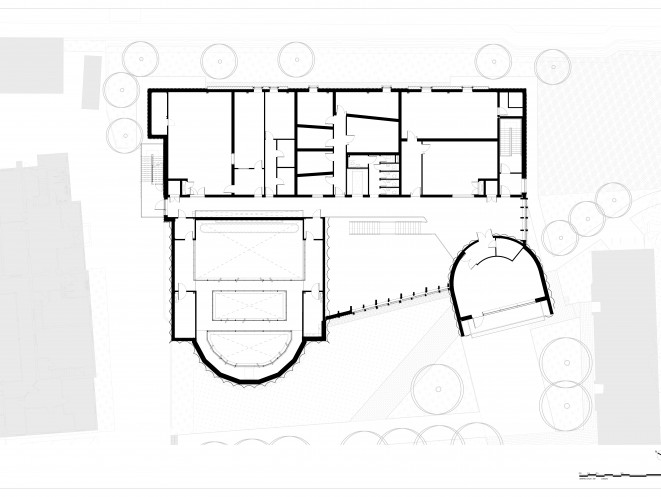

An ongoing project which is probably the most restricted site we are working with has also led to some of the most creative solutions we have achieved to date. The Brunel Museum in Rotherhithe is situated at the southern end of the Thames Tunnel. This was the first tunnel under a river; the last project by Marc Brunel and the first project by Isambard Kingdom Brunel who then went on to create the most famous elements of Britain’s Victorian infrastructure. The tunnel is still in use today by trains, but as the tunnel existed before the rest of the Underground network there are no flood doors. The site is therefore a key piece of heritage, a live piece of railway infrastructure, and a massive flood risk on the banks of the Thames. We have been working with the museum since 2015 on a masterplan to create an immersive museum experience on the site, within the Tunnel Shaft and Engine House buildings, as well as the surrounding landscape. A technique we have developed in response to this is that of the ‘minimum intervention possible’. For example in Phase 1 of the masterplan, which was completed in 2017, we converted the below ground Tunnel Shaft to a museum performance space. As we were only allowed to cut a single doorway into the wall of the shaft for access we decided to create a freestanding staircase element which provided all the circulation, lighting, power, data and theatrical rigging points. The staircase was pre-fabricated in sections small enough to fit though the new access door. This ‘minimum’ approach allowed the powerful patina of history on the walls of the shaft interior to remain fully intact and comprehensible. We are now commencing Phase 2 of the masterplan using a similar approach, stripping out all the visitor facilities from the Engine House (WCs, shop, ticketing etc.) and locating them in a new-build small entrance pavilion, so that you can read the historical narrative of the building’s interior spaces. I must confess that the idea of a ‘minimum’ approach came from a previous and very different project of ours, the Rainforest Canopy Walkway at the Eden Project where we worked with SKM Anthony Hunts to create a pre-fabricated walkway system that would not put undue pressure on the rare tropical trees.

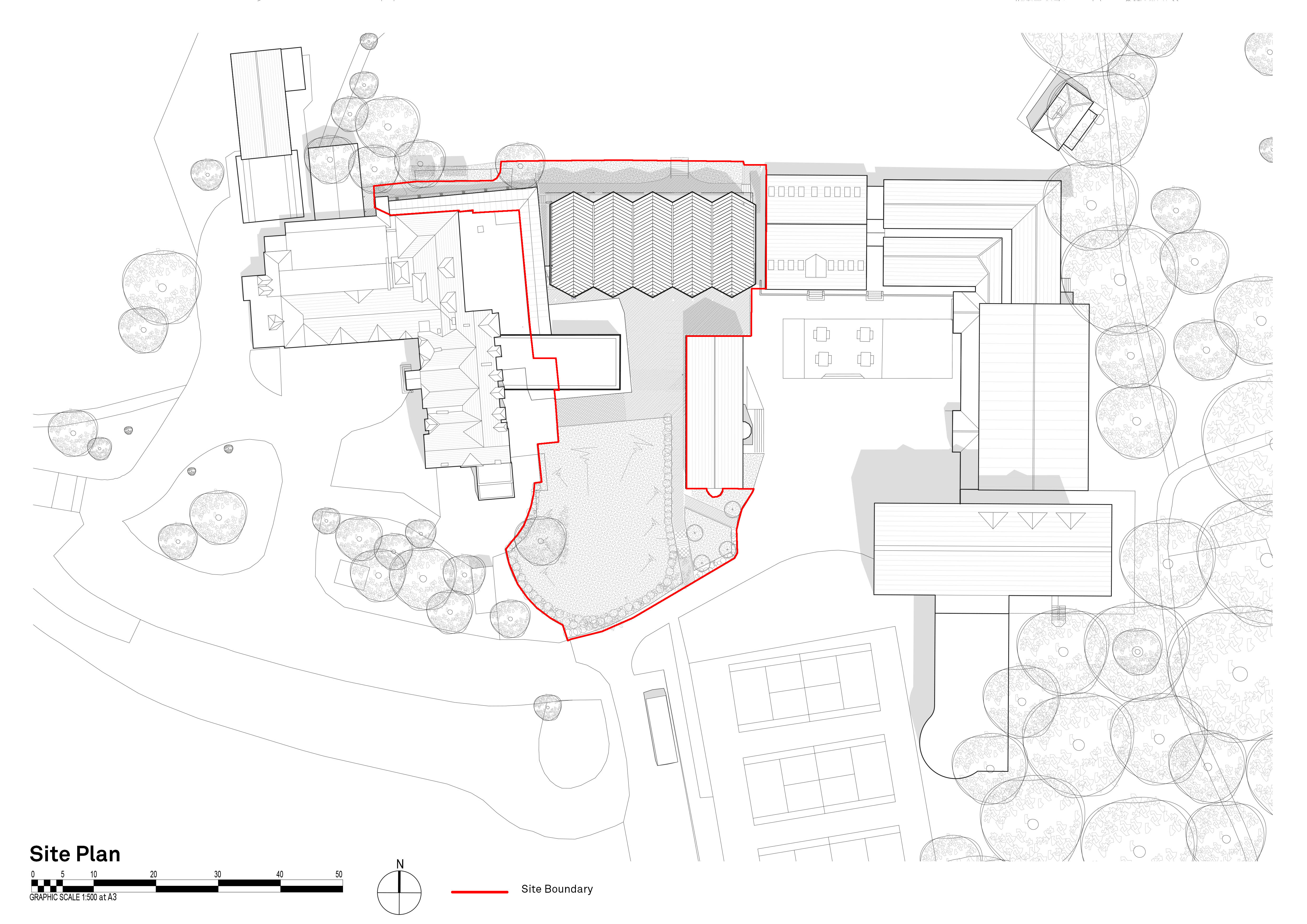

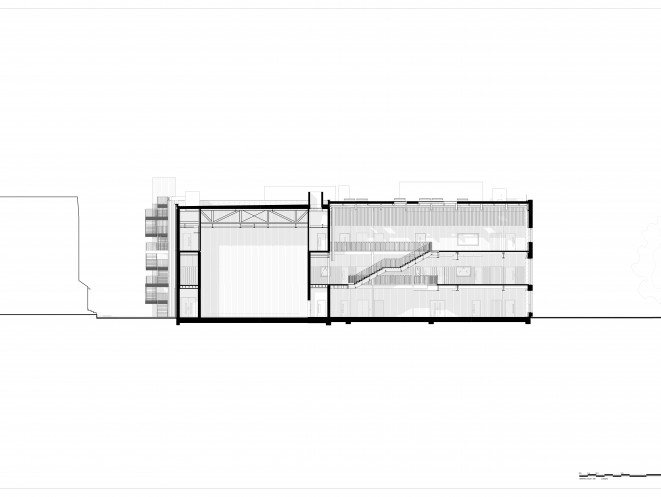

The work with Brunel and The Eden Project has been both technically challenging and conceptually rewarding, but the most ambitious and complex building we have completed to date is the York St John University Creative Centre. This provides a wide range of facilities for creative subjects including a 186 capacity auditorium, recital hall, music rooms, workshops, computer labs and TV studios. The key concept for the building was to promote cross disciplinary collaboration between students, so to link all of these disparate elements together we designed a three storey atrium space. Importantly this was a space for lingering and talking, not just moving through, so we created a series of smaller linked spaces, all wrapped by a warm timber-framed enclosure. This provides a new ‘living room’ for the university; a ‘third’ un-programmed space for students. It also acts as a key element in the environmental control of the building, heated by excess heat from the teaching spaces and naturally ventilated to draw air through. Combined with super-insulation and triple glazing the building is both very low in operational carbon emissions and was constructed for a relatively low embodied carbon figure (both of which the university and student community were passionate about). We embedded the new building into its’ local context, both directly through a new campus landscape masterplan and by visually referencing the adjacent York Minster in the historical centre of the City of York. The heavily serviced nature of many of the spaces in the building, the tight campus site, the heritage restrictions on planning and the ongoing pandemic during construction have all been huge challenges to overcome. The high sustainability ambitions we had for the building, combined with a tight budget, were a further challenge. But by constantly referencing the fundamental principles of our design approach, thinking about community, nature and shelter, the new building has become a catalyst for a transformation of the university campus a new cultural asset for the City of York.

As a practice, and a profession, it is important for us to be constantly developing tactics to find our way through practical restrictions, whilst at the same time keeping the touchstone of our fundamental principles for design; community, nature and shelter. We need to successfully blend both of these together to become sophisticated and intelligent designers of the built environment. In the end the function of architecture is to balance the competing needs of a project to create a building that works, but the art of architecture is to create something which moves the soul.